Sexual Assault on Campus: How far has ANU come?

Sexual Assault on Campus: How far has ANU come?

CW: Sexual Assault & Harassment, Institutional Betrayal

By Orietta Fitzsimmons & James Day

The 2021 National Student Safety Survey (NSSS) revealed that amongst Australian universities, the ANU had the highest prevalence of sexual harrassment and the second greatest amount of sexual assault.

26% of ANU students reported being harassed, twice the national average whilst 12.3% reported they were survivors of sexual assault, which is three times the national average.

The Women’s Department has described these results as “distressingly similar” to those of the 2017 Change the Course Report, which was conducted by the Australian Human Rights Commission and represented the first national report in sexual assault and harrassment at Australian universities. Both the 2021 survey and 2017 report show no change in ANU’s ranking in having the highest prevalence of sexual harassment, and second greatest amount of sexual assault.

Whilst Women’s Officer Avan Daruwalla laments the lack of progress exposed by the NSSS, she wants survivors to know that the process for handling allegations at ANU has massively improved in recent years. She credits the new Registrar, Scott Pearsall, with improving the outcomes of investigations so complainants receive their results within 2-3 weeks instead of months.

According to university data, the average time to finalise official reports of sexual misconduct in 2021 was 27 working days.

Daruwalla also praised the “highly qualified” Student Safety and Wellbeing Team (SSWT) introduced in September 2021 to deal with SASH complaints. With the SSWT, the time taken to respond to disclosures has been reduced from 72 hours to 24.

However she believes that the new SSWT were not advertised sufficiently, critiquing the posters with “psychedelic hands” as “vague”.

Figure 1: Created by Gina Kiel who was commissioned by ‘independent creative agency’ Supersolid for the ANU’s ‘Reach Out’ campaign with the intention of advertising the SSWT.

According to the blog for artist based agency ‘Chulo Creative’ where the images are featured, “Gina was given the brief to create artworks inspired by an expression of togetherness and support in a moment of need”. The stickers allow students to “directly access university support services” by tapping their phones on them, which functions through ‘Near-Field Communication’ (NFC) technology.

Yet, according to Daruwalla, even these were better than the “insensitive” first options put to the ANU by an external PR firm. Among these first options was a sticker of an eggplant emoji emblazoned with ‘unwanted?’, and pillows with links to support services on their underside.

Figure 2: Avan Daruwalla, ANUSA Women’s Department Officer (2021-Present).

Daruwalla also alleges the Respectful Relationships Unit (RRU), the university’s body for anti-SASH advocacy and education, wasn’t consulted on that campaign, which she believes speaks to how “everything is so fragmented” in the University’s SASH response.

Fragmentation was a key issue raised by Daruwalla who criticised the subjectivity of the reporting process. “It really depends on the head of Hall. If the head of Hall is that active ally and someone who cares really deeply about this issue, then they can do a lot more to make the safe space safe for survivors”, she said.

“But if that’s someone who maybe is a victim-blamer, or maybe has less understanding of the system, or even less understanding of sexual assault [and] sexual harassment in the first place, they often are really neglectful and they do very little to support survivors.”

“In those sorts of incidents, we see a lot more instances of survivors having to leave their residence, or even having to leave uni.”

Prevalence of Reporting

According to the university’s 2022 Sexual Misconduct Reports and Disclosure Report, disclosures of SASH increased by nearly 50% from 2020 to 2021.

250 online disclosures of SASH were made to the ANU from October 2019 to October 2021, which increased to 355 the next year. Further, the number of official reports made increased from 9 in 2020 to 31 in 2021. The university has attributed the rise in reports to increased awareness of its online disclosure system.

The University was originally critiqued by victim-survivors due to the length of the disclosure tool, which then contained 66 questions for survivors to answer. As of 2022, the disclosure platform only contains 4 questions.

In response to the NSSS, the university noted that a greater percentage of ANU students were aware of disclosure and reporting pathways for SASH than the national average.

ANU once acknowledged the NSSS as the “single source of truth regarding the prevalence of sexual violence at ANU”. According to the NSSS, both disclosures and reports represent only a fraction of actual SASH incidents. Despite improvements, only 18.6% of survivors seek support or assistance from their universities, with an even fewer 3.3% of survivors making an official complaint.

Daruwalla believes that the university has used greater student awareness to foster the “false narrative that because there is higher reporting, [ANU] a safe place to be”.

“I also think people are more comfortable reporting because we’ve been such vocal advocates in the past couple of years, and we’ve made such a big deal out of this”, Daruwalla asserted in reference to student leaders of ANU. “And people are a little bit more literate about what isn’t appropriate. But I just think that the notion that ANU is a safe place to be is such a lie, and it’s a scapegoat.”

Student Safety and Wellbeing Plan

In his response to the NSSS, Vice-Chancellor Brian Schmidt described the results as “painful and deeply disturbing”, and restated the university’s commitment to an expert-led, best practice response to SASH.

Two days before the anticipated NSSS results release on 23 March, the University released an incomplete initial version of the Student Safety and Wellbeing Plan (SSWP). The Plan outlined how the university seeks to improve prevention and response mechanisms for sexual violence, with a $3.3 million investment into services announced and reported throughout the media.

The Plan describes its approach as informed by the recommendations from Australian Human Rights Commission’s Change the Course Report and the Lyn Walker Independent review of the ANU Sexual Violence Prevention Strategy (SVPS).

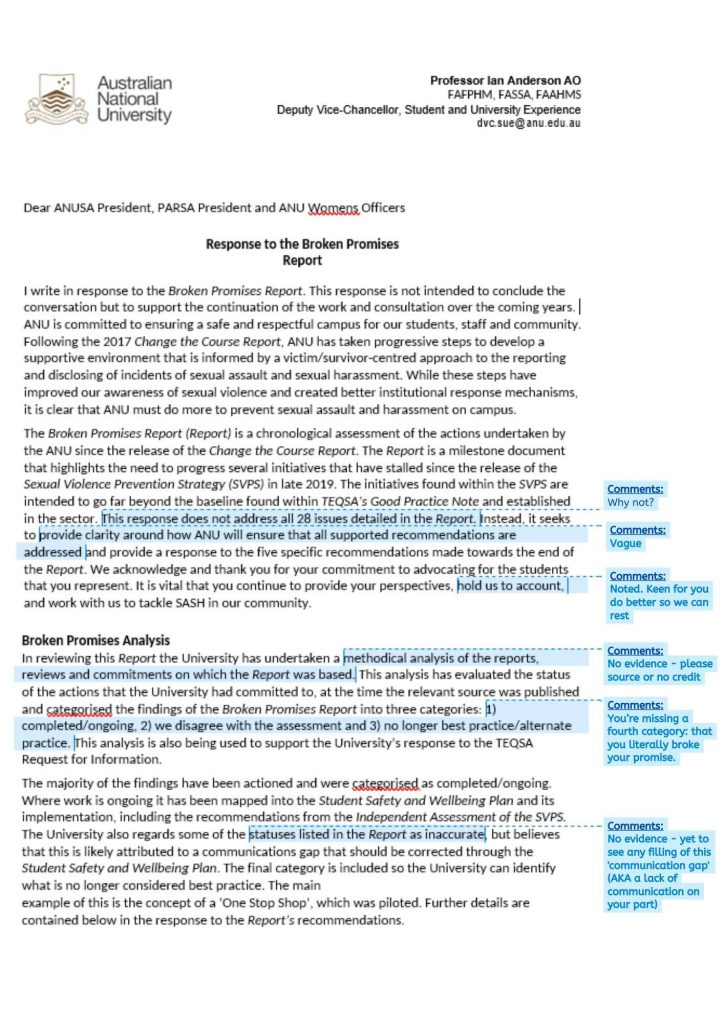

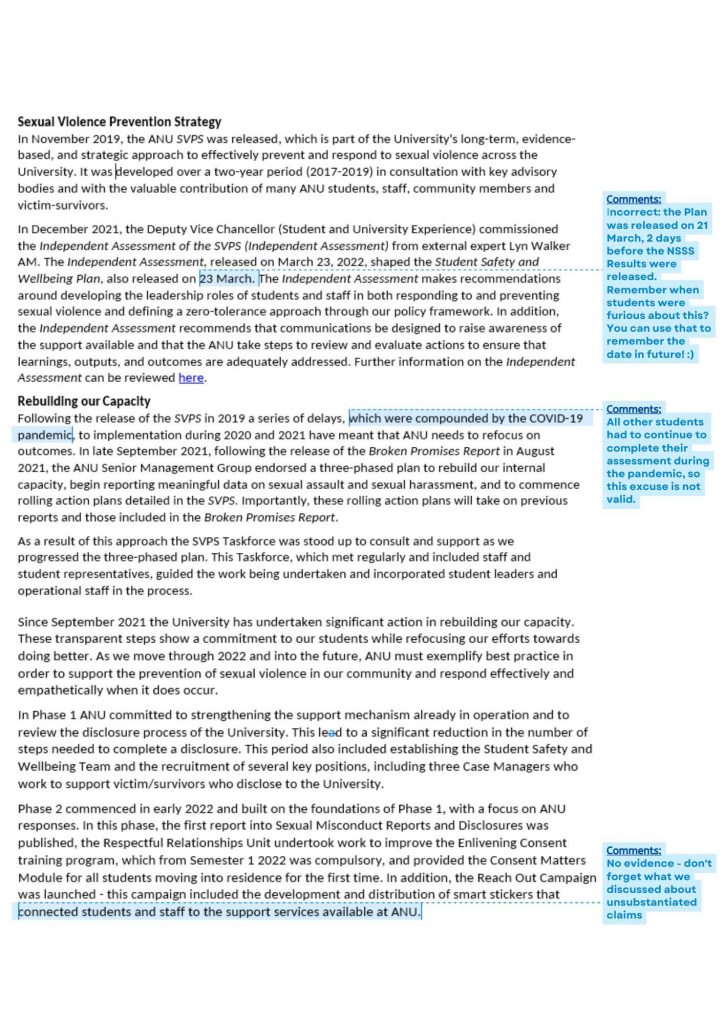

In its response to the Women’s Department’s Broken Promises Report, the University acknowledged that there have been “significant delays in implementing the SVPS, which were “compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic”. It believes that these delays in communication led to the Women’s Department finding that the University had failed to complete 28 anti-SASH initiatives.

The university placed the Women’s Department’s assessment of their supposedly incomplete initiatives in three categories; completed or ongoing, no longer best practice, or simply “disagree[ing] with the assessment”.

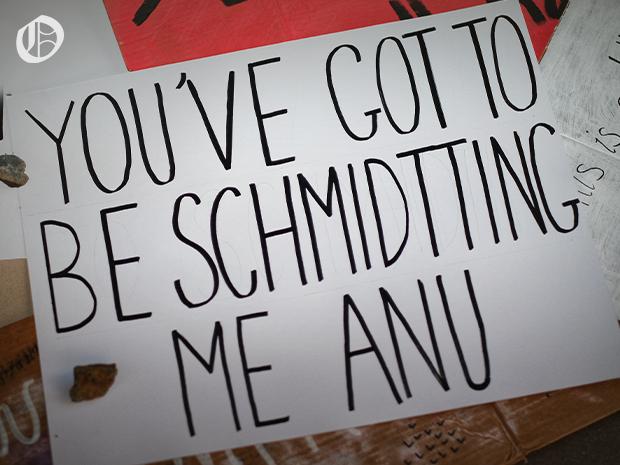

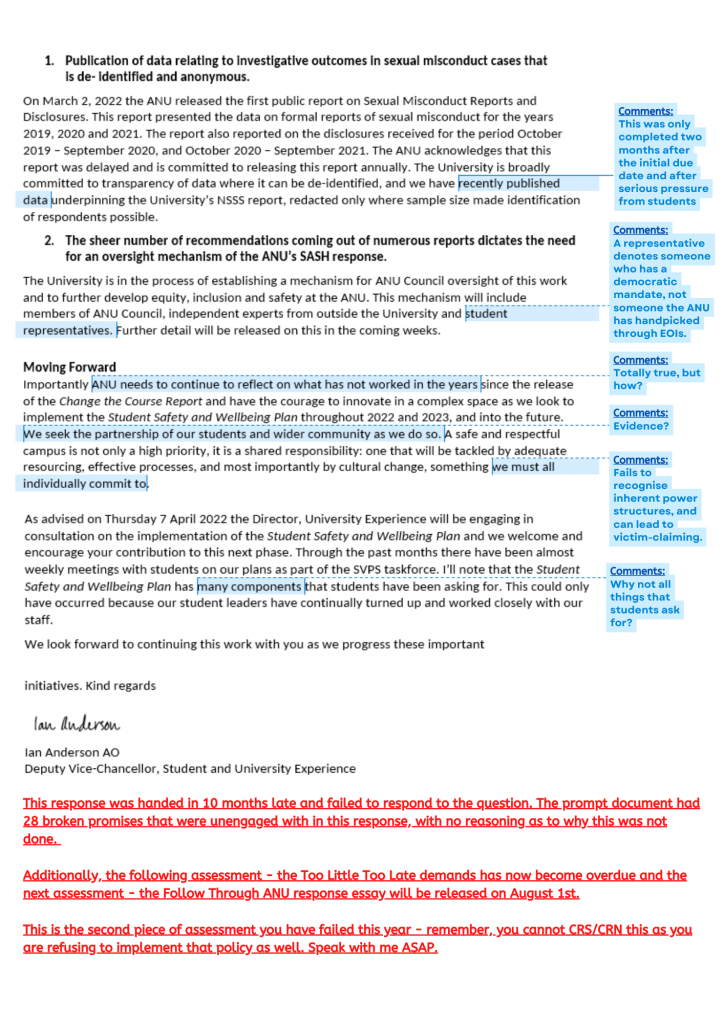

Overall, the majority of initiatives were classed by the University as complete or ongoing. On 31 July, the Women’s Department released its own ‘grading’ of this report, marked-up with criticisms of the document and including the comments “This response was handed in 10 months late and failed to engage with the questions”.

Updates on the SSWP rollout are included in the monthly ‘On Campus’ Newsletter, and the fully completed Plan was released on 26 July.

The university states that it has consulted with over 200 stakeholders, including students, and that the Plan “puts an onus on tangible outcomes and a pathway forward for a safer campus.”

The finalised Plan is much more specific than the first edition, containing updates on the ‘Activity’, ‘Key Actions’, ‘Responsible Officer/Group’, ‘Scheduled Finished’, and ‘Outcomes/Update/Comments’. According to the ANU, the Plan will be fully implemented by Q1 2022.

Phase 1 of the Plan was focused on rebuilding support mechanisms and the disclosure process. Phase 2 focused on continuing to improve the quality of the response mechanisms. Phase 3 is currently underway, and is focused on “further strengthening of ANU initiatives in education and prevention, reporting, disclosures and case management, and institutional response and reporting”.

As part of this, the University aims to enforce a zero-tolerance approach to sexual violence, increase student engagement, strengthen support services and enhance students’ understanding of support processes.

Pastoral Care

One of the key focuses of Phase 3 of the Plan are residential halls, where 25% of ANU’s student population resides and a disproportionately high level of sexual assault incidents occur.

Broadly, Daruwalla has expressed a sense of betrayal toward the on-campus lifestyle she and many other students had been sold. “I feel like I was really sold this living on campus dream, like it was going to be so fun and so exciting. But it’s actually dangerous and scary.”

As part of their efforts to redress the SASH incidents on-campus, a significant proportion of the millions committed to the SSWP will go towards hiring 14 new pastoral care staff at residential colleges.

As part of this, the university commenced a pilot of the Residential Community Safety Officer program on 27 July. According to the Plan, “the Officers will work in pairs and provide additional safety and support to residential students between 6pm and 6am, Wednesday to Saturday.” Pending assessment, the program may be expanding to all on campus residences in 2023.

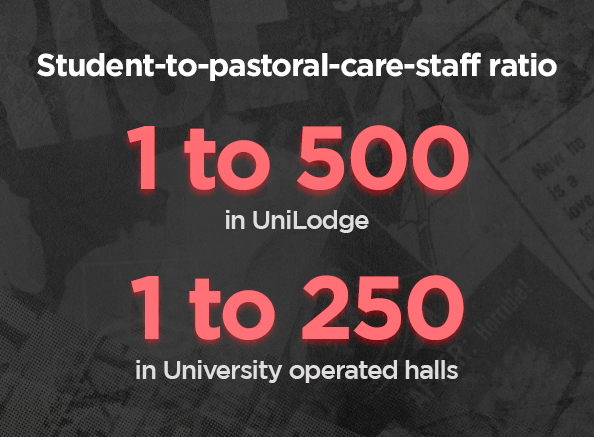

The Women’s Department has been particularly critical of the outsourcing of pastoral care. UniLodge, which is home to over 2500 ANU students, has only 6 full-time pastoral care staff, who also have administrative responsibilities. According to the Women’s Department, this leaves UniLodge with a student-to-pastoral-care-staff ratio of 1 to 500, as compared to 1 to 250 at University-operated halls. The Women’s Department has demanded the number of pastoral care staff at UniLodge be at least doubled to reflect that ratio.

Daruwalla believes that because of UniLodge’s for-profit model, the staff are paid and trained less than ANU’s. The resulting lack of trust between students and UniLodge pastoral care staff ultimately leaves Senior Residents (SRs) to assume a “disproportionate burden… without appropriate training or support”, according to her.

With the opening of SA8 approaching, the Women’s Department has also demanded that the ANU “immediately commit to a high level of pastoral care”, including “a commitment to not outsource pastoral care”.

The outsourcing of pastoral care disproportionately affects international students, who comprise a large proportion of UniLodge’s cohort. The NSSS showed that international students were less likely to report experiencing sexual harassment, but that when that did, they were more likely to make an official report to the university. However, it also revealed distinct challenges pertaining to cultural attitudes around sexual violence and a heightened fear of getting in trouble.

This was reflected in the experience of SSWT Case Manager Katerine Kuntz, who described international students as often “scared of losing their visas”.

The NSSS also identified Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, LGBTQIA+ people , people living with disabilities and culturally and linguistically diverse people as disproportionately victimised demographics. The complete SSWP states the objective to cater to the needs of students from “varying ethnic backgrounds”.

The Plan has also expressed its intent to improve support mechanisms for all SRs through improving clinical supervision, and is also piloting a debriefing service for SRs.

The Respectful Relationships Unit

One of the University’s most prominent initiatives is the Respectful Relationships Unit (RRU), established in 2019. The RRU describes its role as “the prevention of sexual assault and sexual harassment in the ANU community” through “education, community engagement, capacity building, consultation and planning facilitation”. Whilst it originally dealt with both advocacy and response, it has been tasked solely with advocacy since the establishment of the Student Safety and Wellbeing Team in 2021.

Daruwalla believes that historically, the University has used the RRU to deflect criticism. She said that “whilst [the RRU is] a great idea in theory, in practice it does very little”.

She spoke critically of ‘Consent Matters’, the online consent modules compulsory for ANU students. Alison Henry is the Managing Editor of the Australian Human Rights Journal, currently completing her PhD candidacy with the Australian Human Rights Institute.

Henry describes ‘Consent Matters’ as a “tick it and flick it”, instead of requiring ongoing and in-person training. Henry says it is essentially “employed by universities not due to any proven efficacy but because it’s an easy thing they can roll out at a low per-student cost”.

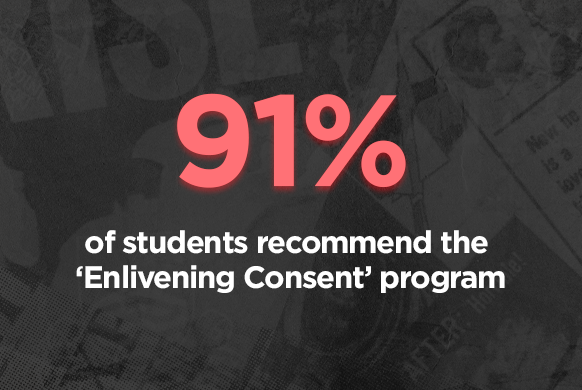

The RRU also runs the ‘Enlivening Consent’ Program, an hour-long in-person talk compulsory for residential students. Student evaluation feedback has shown that over 91% of students would recommend the program.

Of ‘Enlivening Consent’, Daruwalla said, “they always say it’s to start a conversation, and we’ll have more conversations throughout the year. And then that doesn’t happen. And I also think that they are going to engage with the people who already understand consent … there needs to be campaigns targeted at perpetrators”.

If one thing, Henry believes the NSSS has shown universities that they must meaningfully rethink their current approaches to SASH.

“My overall assessment of that report was, you know, despite all the effort that’s been made – and there has been a lot of effort – it hasn’t shifted things yet. I think you need some sort of intervention.”

The Student Safety and Wellbeing Plan represented an intention to change the University’s SASH prevention framework. The Respectful Relationships Unit worked to improve the consent training in Semester 1 2022, and the University has committed to a new consent course for 2023 based on best-practice models. This will include face-to-face training for all students, to “make it more than just a tick-box” according to Brian Schmidt.

Whilst the RRU declined to provide a broader comment to Observer, its manager Joel Radcliffe expressed concern about “constant criticism levelled at RRU which seems to directly undermine our work and ignore ongoing attempts to engage students in constructive ways”.

“I’m all for students holding the university accountable at a governance [or] strategic level, but criticising a team of passionate specialists who have been set up to drive change seems petty and counterproductive. We’ve been burnt in the past, hence my reluctance”, Radcliffe said.

The SSWP called for a new Steering Group that includes university staff and three student representatives.

The traditionally cyclical nature of student activism was cited as a challenge to progress by both Daruwalla and Henry. According to Henry, typically “it ends up being back with agitators”. As in, students continue to be the primary activists. In her view, Women’s Officers nationally suffer vicarious trauma from supporting survivors and are not personally well supported in their roles.

One of the 2021 Women’s Officers, Priyanka Tomar, previously stated in the Broken Promises Report the stress of trying to communicate with the University and receive disclosures left her “emotionally drained” and that “ultimately, the role became so unsustainable, I had to leave my term mid-way.”

This perspective is reflected in Daruwalla’s experience, who was “shocked at the level of disclosure” she has received across her two years as Women’s Officer. She said that despite improvements to the reporting process “there are a lot of students who feel like they don’t know where to go”.

“Personally I feel that my time in this role has left me a lot less happy, a lot less optimistic,and pretty sad”, Daruwalla said.

Follow Through ANU

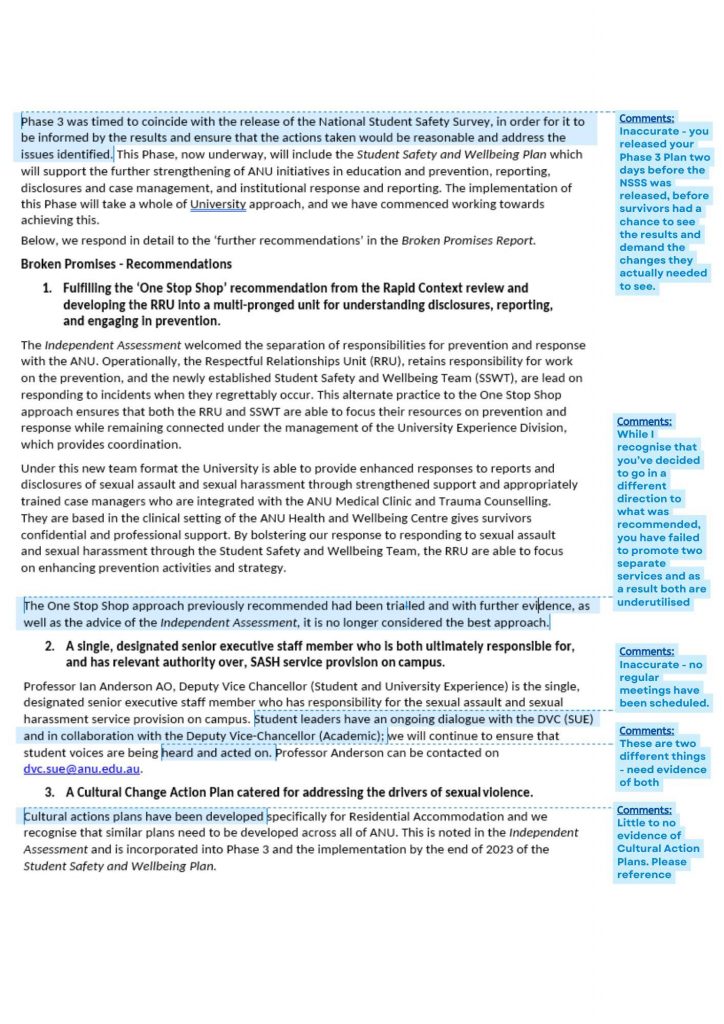

Following their request that the ‘Too Little, Too Late’ demands receive a response by 1 August, the Women’s Department held the ‘Follow Through ANU’ teach-in and protest, to deliver a new report to the Chancelry. Key demands of the report are the “the creation of an actionable Cultural Change Action Plan”, and “engaging with the intersectional aspects of SASH”, which student leaders allege the current Plan fails to do.

Figure 3: Protesters walking along Sullivans Creek.

The teach-in guests applied intersectional perspectives to SASH issues, and the SSWT and RRU explained their roles. This was followed by a ‘feminist consciousness raising’ activity, where students shared their experiences with gendered violence.

Regarding their reasons for being there, one student said “a lot of stuff at college has really hit home and there’s not been a lot of change”.

“I was an SR last year at Wamburum Hall [and I] got far too many disclosures than I should have and witnessed too many of my friends become survivors”, another student said.

Student leaders and survivors expressed their frustrations at what they perceive as inaction by the ANU.

“I don’t want to run another protest”, Daruwalla said in her speech. Directed at ANU, she said “we have all the ideas, just speak to us”.

The protest then walked to the Chancelry, where they blocked the entryway with banners and bollards.

Figure 4: Students fortified the barricade at the door of the Chancellery after no response from ANU VC Brian Schmidt.

In response to ANUSA’s claims, a University spokesperson stated “We continue to work with survivors, advocates and experts on our response to this difficult issue. We have accelerated our work and our investment in tackling this problem, which has no place here, or in society.”

”We are committed to ensuring ANU is safe and inclusive for everyone”.

This piece is the first in a two-part series entitled ‘Sexual Assault on Campus’. The second piece, on the legislative shortcomings slowing SASH progress and the possible financial incentives informing it, will be released next Tuesday 16 August.

Graphics by Will Novak

Photography by Mackenzie Watkins & Patrick Guthridge

If this article has raised any concerns for you, or you have been affected by its content, there is support available:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Beyond Blue: 1800 650 890

Canberra Rape Crisis Centre: 6247 2525 (7am–11pm) or 131 444 (after hours)

ANU Wellbeing & Support: 1300 050 327

ANU Counselling: [email protected]