The ‘Johns’ | Explaining Campus Building Names Vol. 2

By Brandon How

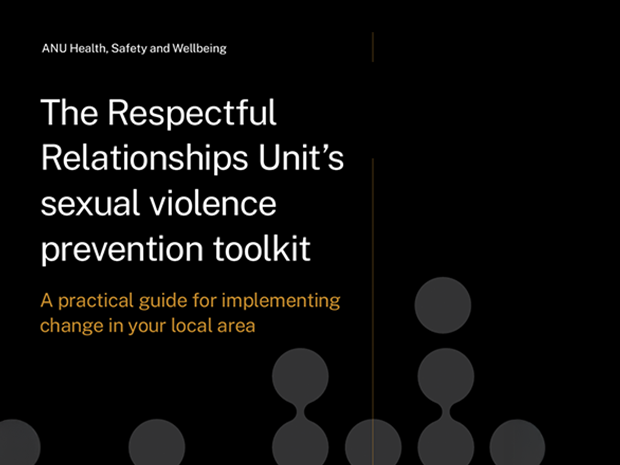

It goes without saying that not any ‘Tom, Dick or Harry’ will have their name honoured on an ANU building – but apparently being named John puts you in good stead. Of the 48 non-residential buildings on campus, 7 are named in honour of men whose first name is John, the most of any first name and more than the number of women who are honoured. In this article, Observer is dead-set on identifying these John Does.

Graphic by Brandon How

John Curtin (1885 – 1945)

John Curtin giving a speech

The John Curtin School of Medical Research can be found at 131 Garran Road. It also houses the Jackie Chan Science Centre, named after the movie star who is also a benefactor of the University.

According to the University, the Research School was named after Curtin “as early as 1945”. This was done to acknowledge “his foresight in inviting” Oxford University professor, Sir Howard Florey, to Australia. After Curtin’s death his successor, Joseph Benedict Chifley, “continued Curtin’s legacy” and invited Florey to be the foundational head of the research school.

As Australia’s Prime Minister during the Second World War, John Curtin is likely a familiar name to many, even if the details of his life may not be. The Australian Dictionary of Biography describes him, in brief, as “a natural Australian, impervious to Imperial ideology”. Originally from Creswick, Victoria, Curtin would eventually hold the Federal seat of Fremantle, Western Australia for a total of 14 years.

Curtin joined the Victorian labour movement at a young age, and eventually moved to Western Australia in 1917. There he became the editor of the Westralian Worker, a union movement newspaper, where he wrote hundreds of articles and editorials. After three failed attempts, Curtin won the Federal seat of Fremantle in 1928, and was eventually elected leader of the Labor Party in 1935.

Following Britain’s declaration of war on Nazi Germany in 1939, Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies soon followed suit. In light of the war, Menzies repeatedly invited Curtin to form a national unity government, but was roundly rejected as Curtin feared the Labor party would not fully support him. A cross-party Advisory War Council was formed as a compromise in 1941, but Menzies’ support within the ‘United Australia Party’ was ailing. This led to his resignation at the end of August. In October, the Government eventually crumbled when the two independents propping up the governing coalition voted against the budget. Curtin became Prime Minister on 7 October despite Labor not holding a majority in the House of Representatives, as a wartime election was considered too destabilising.

Having won power at home, he then had to face the British and American Governments, as both wanted Australian troops to fight on more fronts. In 1942, the British in South-East Asia had put all their eggs in one basket by pursuing the ‘Singapore Strategy’. They had hoped that by making Singapore an ‘impregnable fortress’, it would be able to repel any potential Japanese attacks in the region, including against Australia. However, on 15 February 1942, Singapore was captured by the Japanese after just a week of fighting. The following day, Curtin announced in a radio address to the nation that “the fall of Singapore… can only be described as Australia’s Dunkirk. It will be recalled that the fall of Dunkirk initiated the Battle for Britain. The fall of Singapore opens the Battle for Australia”.

After the fall of Singapore, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had repeatedly attempted to redirect Australian forces to help defend Burma (now Myanmar). Churchill at one stage bypassed Australian command and ordered the British Admiralty, who were transporting the troops, to change their course to Rangoon. Curtin later demanded that they be returned, reportedly saving the diggers there “from almost certain destruction”. By May the Japanese had expelled Allied forces from the country. After this, Curtin suspected that Churchill regarded Australia as “expendable”, and began to work more closely with American General MacArthur in the Pacific Theatre.

[seated, from left to right] Winston Churchill, John Curtin

As the war progressed, the stress of war leadership began to take its toll on Curtin. On 5 July 1945, as the National Museum of Australia put it, “he died from ‘war-weariness’, over-exertion, stress and heart disease”. This was just one month before the end of the war.

John Crawford (1910 – 1984)

A photo of John Crawford

The J.G. Crawford Building can be found at 132 Lennox Crossing. It houses the Crawford School of Public Policy and the office of the Australia and New Zealand School of Government.

Sir John Crawford was an influential Australian public servant and later a fixture at the ANU. His life as a senior public servant began during the Second World War, when he spent two years serving in the Department of Post-War Reconstruction under HC ‘Nugget’ Coombs. He then spent the next 15 years at a number of departments, earning his place as one of the ‘Seven Dwarfs’, an informal collection of seven public servants of small stature but big influence in policy making. Reportedly, the Commonwealth Club would be frequented by the ‘dwarfs’ as one of the “bastions” that hosted the “jostling of the many” senior public servants. On occasion, even Crawford would joke about the difficulty he encountered when shopping for a shirt that fit him.

In 1960, Crawford finally joined the ANU as an economics professor and the Director of the Research School of Pacific Studies. Reportedly, “the school had been in some disarray” until Crawford “took firm control”. Crawford’s work led to the founding of a number of research units, including the Contemporary China Centre (now the Australian Centre for China in the World), New Guinea Research Unit, and, the now leading journal on the Indonesian economy, the ‘Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies’, to name a few.

Crawford was Vice-Chancellor of ANU from 1968 to 1973, and then Chancellor from 1976 to 1984. While in office, he oversaw a turbulent time of persistent student activism, namely against the Vietnam War. Despite these challenges, Crawford strove to strengthen the relationship between students and the University. During Crawford’s tenure, the ANU Council first introduced positions for student representation, and he resisted official attempts to access the profiles of students involved in anti-war activism. His obituary illustrates his tirelessness, describing him as achieving the equivalent of “work for two or three men”, a feat that he “enjoyed”.

True to his fervent work ethic, Crawford initially only took on the ANU professorship on the condition that he would be allowed to continue his involvement with the Government in an advisory capacity. As a result, Crawford’s profile as a policy maker as well as an economist continued to grow, leading to his pivotal role in the establishment of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) as a close advisor to Bob Hawke. APEC is an economic forum with 21 member states and aims to promote free trade. He also advised the World Bank, and a number of other economic organisations.

In ‘The Seven Dwarfs and the Age of the Mandarins’, Crawford is described as “essentially fair-minded”. He was also known to speak with “restrained bitterness” about “those bureaucrats to whom the poor and the unemployed were not persons but simply component figures in a statistical index”.

John Carver (1926 – 2004)

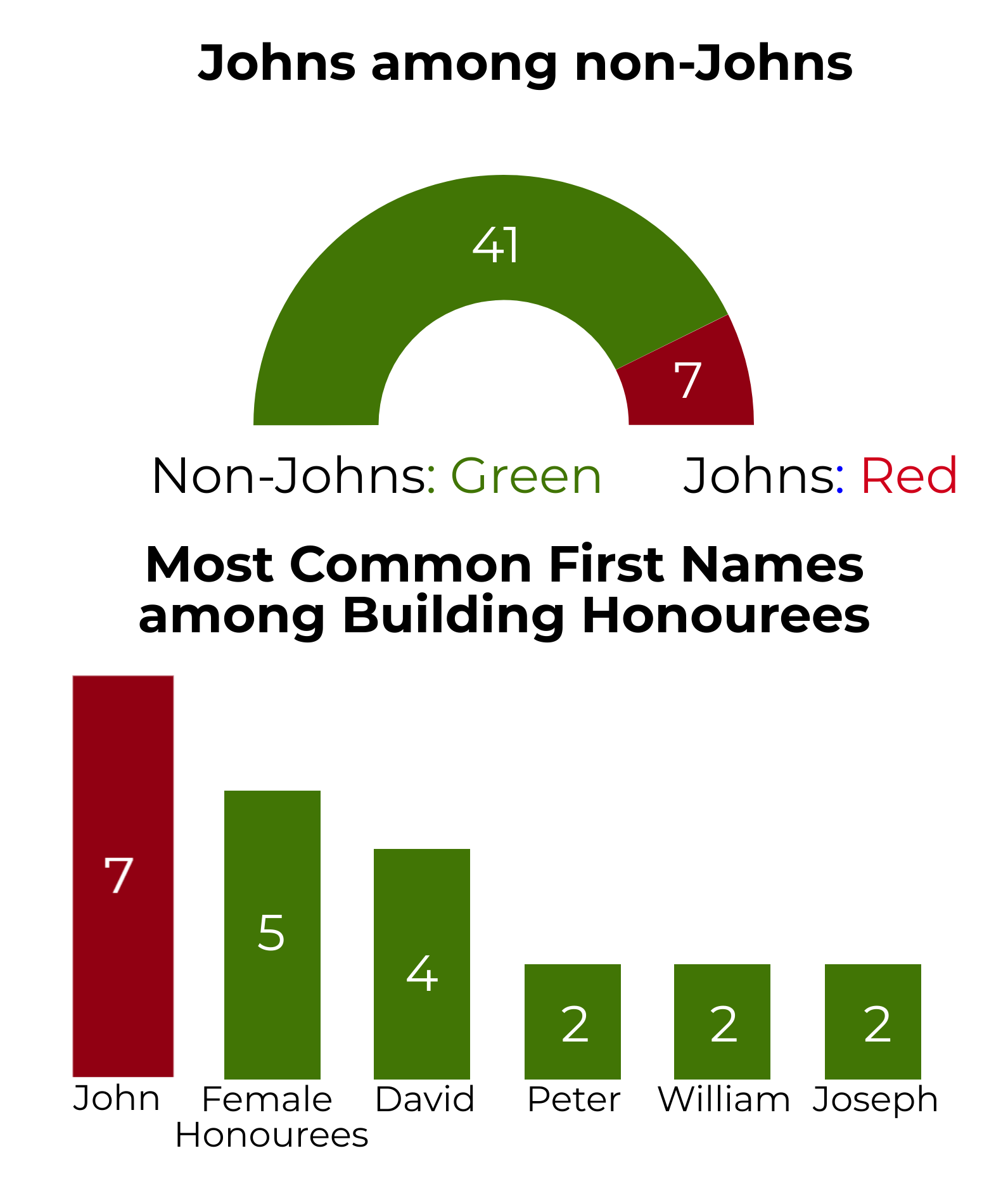

[from left to right] John Carver VI, John Carver VII, John Carver VIII in the John Carver Building

The University has had the pleasure of being affiliated with three different John Carvers. The building itself is named after John Carver VI. He is not to be confused with his son, John Carver VII, who was director of the Research School of Chemistry from 2013-2019, or his grandson, John Carver VIII, who completed his Master of Finance at ANU in 2017.

Carver VI, henceforth just Carver, was a foundational member of the Research School of Physical Sciences. His ANU career stretched across four decades. In 1949, Carver received an ANU Travelling Scholarship to complete his PhD at the University of Cambridge, as at this time there was no physical ANU campus for him to attend. In an interview with the Australian Academy of Science (AAS), Carver recalled the optimism the ANU Travelling Scholars had shared during their time overseas. They had anticipated that after returning to Canberra “in two or three years time” they’d have “discovered the anti-proton, [gotten] Nobel Prizes and [retired] for the rest of [their] lives”.

From 1978 to 1992, Carver was the Director of the Research School of Physical Sciences (now Physics), and was influential in shaping the School’s various departments. During his time, Carver emphasised the role of engineering in the School, introducing departments in Optics, Electronic Materials Engineering, Systems Engineering, and the Atomic and Molecular Physics Laboratories, to name just a few. From 1970, he was also the Chair of the UN Scientific and Technical Sub-Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, a position he held for 26 years.

Carver also founded ANUTech (now ANU Enterprise) which, according to the ANU archives, was the University’s “commercial and technical arm”. The company primarily dealt with the promotion and “application of discoveries and inventions originating in the university”. In an interview with AAS, Carver shared his belief that the University would not receive a “substantial increase in government handouts from either party in Australia” and would have to find other ways of “increasing the funding and expanding it”.

In Fire in the Belly, a book that details the history of the Research School of Physics at ANU, Carver’s “greatest attribute” is described as his ability to “manipulate the fashions of the times and trends of University policy…always to the advantage of the school”.

John Cockcroft (1897 – 1967)

A photo of John Cockcroft

The John Cockcroft building houses the Research School of Physics, and can be found at 60 Mills Road.

British physicist Sir John Douglas Cockcroft was the ANU Chancellor from 1961 to 1965, but is best remembered for winning the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1951 alongside Ernest Walton. This was in recognition of their earlier 1932 experiment, through which the pair became the first to artificially split an atom. Cockcroft’s time as ANU Chancellor was largely uneventful, as he was also concurrently the head of Churchill College at the University of Cambridge. In fact, according to the Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, he only spent a “few weeks each year” at ANU.

During the First World War, Cockcroft fought on the Western Front as a member of the Royal Field Artillery. During the Second World War, he took on a more cerebral role as Director of the Atomic Energy Division at the National Research Council of Canada. According to Britannica, in 1946 he became director of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) at the Ministry of Supply.

While in his role at the AERE, he oversaw the opening of the first nuclear reactor in Western Europe at Windscale (now Sellafield) in North West England. He had insisted that the chimney stacks of the facility have filters installed. This was widely mocked by the facility engineers at the time because the reactor process did not emit any particulates. The BBC has reported that they were labelled “a waste of time and money” and were nicknamed “Cockcroft’s Follies”. This was until 1957, when a reactor core caught fire and began to release radioactive material. Had the filters not been installed, the BBC noted that “the radioactive dust blasted into the air would have been much more devastating”. One of Cockcroft’s physicists also attested that “the word folly did not seem appropriate after the accident”.

Throughout his life, Cockcroft accumulated honorary doctorates from 19 universities and, according to the Nobel Prize Organisation, was “a fellow or honorary member of many of the principal scientific societies”. Cockcroft has been described as a mild-mannered man, and had six children with his wife Eunice Elizabeth Crabtree.

John Jaeger (1907 – 1979)

A photo of John Jaeger

The Jaeger building houses the Research School of Earth Sciences and can be found at 142 Mills Road.

John Jaeger was the foundational professor and head of the Department of Geophysics (now the Research School of Earth Sciences), and worked at the ANU from 1951 to 1972. During this period, he constantly campaigned for the establishment of a Research School of Earth Sciences, to separate it from the Research School of Physical Sciences, which was finally inaugurated in 1973. At the time of his appointment, Jaeger was the first professor of geophysics in Australia. From 1963 to 65, Jaeger served as Dean of the Research School of Physical Sciences before returning to his role at the Department of Geophysics. This period is described in the Historical Records of Australian Science as a time of “effective management without dramatic highlights”.

During his academic career at ANU, he published over 130 articles and authored or co-authored six books. His own research at ANU was, according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, “mainly in terrestrial heat flow and rock mechanics”, which culminated in “the first comprehensive picture of the regional variations in the geothermal flux in the Australian continent”.

Jaeger worked at the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (now the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) during the Second World War. During this period, he worked on an unpublished study into the temperature reached in the retina when a person stares at the sun. This was supposedly because many anti-air gunners were suffering eye damage.

Although he was among many other Australian scholars at Cambridge University in the 1930s, he was described by some contemporaries as “very shy”. Even so, in 1935 he married Sylvia Percival Rees. However, according to the Historical Records of Australian Science, Jaeger claimed that Rees “insisted on marrying”, and that he had only “married her in a pea soup fog; it was a great mistake”. When his divorce proceedings were finally completed in 1950, he “almost immediately” married Martha Elizabeth Clarke. This matrimony was more successful, and supposedly had “deep meaning” for Jaeger.

John Yencken (1926 -2012)

John Yencken smoking a cigar

The John Yencken Building can be found at 45 Sullivans Creek Road and houses various offices.

John Yencken was a research chemist and administrator who served on the ANU council from 1966 to 1983, and advised on research activities. He was also the first chairman of ANUTech (the company founded by John Carver), and a large benefactor to the University.

Yencken studied Chemistry at Cambridge University from 1943 to 1945 on an accelerated wartime program. Sadly, his father passed away in 1944, midway through his honours examinations. Despite the University offering to exempt him from further examination and pass him, Yencken opted to complete the course and achieved first-class honours. At the age of 79, he completed a PhD from Swinburne University of Technology, and eventually received the Medal of the Order of Australia in 2010 for his research in agri-business.

In his obituary, it is noted that Yencken and his first wife Agnes-Mary Martin shared a love for horseback riding. It seems that this was something Yencken could not bear to do alone, as on the day of Martin’s death in 1983, he reportedly “went for a long ride alone – and then never rode again”. He did, however, re-marry in 1987.

John Gould (1804 – 1881)

An illustration of John Gould

The Gould Building can be accessed from Daley Road or Linnaeus Way, and houses the Research School of Biology.

John Gould was a British zoologist and ornithologist (bird studies), and is acknowledged as the ‘father’ of ornithology in Australia. Throughout his career he published 41 volumes, seven of which comprised his magnum opus, ‘The Birds of Australia’. This particular publication described 328 previously undiscovered species, which were all named by Gould.

At the age of 23, Gould became a taxidermist with the Zoological Society of London. During this time, the task of identifying the bird specimens brought back from Charles Darwin’s expedition fell to him, with his work eventually being referenced in ‘On the Origin of Species’.

Gould first became enamoured with the birds of Australia after he received specimens sent by his brothers-in-law from New South Wales. This interest eventually led to his arrival in Hobart in 1838, accompanied by his wife, Elizabeth Coxen, and their seven-year-old son. Before returning to London in 1940, Gould predominantly explored the Hunter Valley, NSW, but also spent several weeks in the Murray Scrubs, SA. Coxen was a talented artist and was responsible for many of the full-page illustrations featured in Gould’s publications. She produced 84 drawings which were eventually included in ‘The Birds of Australia’ before her untimely death in 1841. Publication of ‘The Birds of Australia’ began in 1840, and was only completed in 1848.

Graphics by Tristan Khaw

Know something we don’t know? Email [email protected] or use our anonymous tip submission.

If you have an issue with this article, or a correction to make, you can contact us at [email protected], submit a formal dispute, or angery react the Facebook post.

Want to get involved? You can write articles, photograph, livestream or do web support. We’re also looking for someone to yell “extra!” outside Davey Lodge at 1AM. Apply today!