Former John XXIII College Chaplain Accused of Historical Sexual Assault

By Darlene Rowlands

Content Warning: express mentions of sexual assault and sexual harassment (SASH), institutional betrayal.

An alleged rapist lived and worked alongside ANU students on campus until as recently as 2013. He was a live-in chaplain at John XXIII College for at least three years, and later an ANU staff member for a separate period of at least six years.

A woman who alleges she is a past survivor of the chaplain’s sexual abuse reported it to the Dominican Order – a branch of the Roman Catholic Church that also owns and operates John XXIII College – in 2008.

By that stage, it was known to at least one senior leader of the Order that the man she accused was working at ANU. In comments to Observer, the leader in question confirmed this. They also confirmed that they consciously did not contact the University when the sexual assault report was made, because “[they] had absolutely no right to do so”.

The survivor reached out to the ANU several years after his employment, in 2018. She requested ANU to make efforts to contact potential survivors of sexual abuse at John XXIII College by the same priest who allegedly abused her, and proposed a series of actions to prevent potential incidents of clergy abuse of students in the future.

Despite initial movement from ANUSA and PARSA student leaders to escalate her report, correspondence fizzled out shortly after she revealed she was not a student at ANU and her assault didn’t occur on campus.

John XXIII College in the 1970s / ANU Archives.

She was never formally invited to meet with senior ANU staff to progress her recommendations, and the policy that saw chaplains at John XXIII College live in close proximity to students remained in place for another two years.

To the knowledge of current ANUSA leadership, the recommendations proposed by the survivor may never have been actioned.

The woman, who will be referred to as Emma, has shared her story – of how she tirelessly attempted to speak out to anybody who would listen, for herself and for other survivors – with Observer.

Emma arrived in Australia alone as a refugee. She escaped after four years of failed attempts, witnessing the captures and injuries of other boat passengers many times over before making it to Australia at 22.

She studied computing at university and settled in a major city, living in a house for female refugees that was owned and operated by the Catholic Church.

After living in the house for a period of time, Emma was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with her living conditions. She sought help, and this is when she claims she met the priest.

He was from the same country as her, and they had grown up with common cultural customs and beliefs. She further claims he became a confidante for her to vent frustrations about her living conditions without judgement. Emma alleges that he sexually assaulted her during this period.

A few months later, when Emma’s living situation crumbled, it was allegedly the priest who found her a new place. She was still a student who was “very desperate, and so afraid of living by myself”, and unable to source accommodation that was within her means. His connections with the Church and parishioners meant he could find somewhere owned by the Church for Emma to live.

Several months more and the priest was leaving for Canberra and she was concerned the Church-owned accommodation he set up for her in the major city would not allow her to stay once he left. “When he told me to move to Canberra, I did because I had no one else”, she said. Emma alleges it was then that he sexually assaulted her for the second time, this time raping her.

“After [he first assaulted me], I thought that I could protect myself if it happened again. So I kept looking to him to protect me.”

Emma was only 24.

Dr Stephen de Weger is an academic from the Queensland University of Technology whose work focuses on clergy sexual misconduct against adults. In his work, he highlights that the inherent power differentials between clerics and laypeople is often not fully appreciated when clerics commit sexual abuse against adults.

Male priesthood is undoubtedly “upheld as the ultimate expression of following Christ”. As a consequence, every individual religious follower possesses significantly less power in juxtaposition to the positional power of priests.

“Within the [Roman Catholic Church], simply being a layperson, especially female, is to be positionally vulnerable with reference to clerics”, Dr de Weger asserts. It is in the context of these power differentials that clergy sexual assault can occur.

Shortly after the move to Canberra, the priest began a new position as a live-in chaplain at John XXIII College, according to Catholic Church records. He remained in this position for at least three years.

A student who lived at the College from 2019 to 2020 described the live-in chaplaincy arrangements to Observer as she remembered them. She said the chaplain’s room only shared a hallway with the College president and one other resident, who was “normally someone paying extra for a large room, or a Johns leader”.

“No one could just unsuspectingly be put in the room next to him”, she said.

John XXIII College in the 1970s / ANU Archives.

When Observer asked John XXIII College about this claim, a spokesperson for the College corroborated it. “It is well known that those rooms are currently designated for positions of senior student leadership, positions which are applied for and highly sought after”.

“Students are aware that these rooms are adjacent to a staff residence”.

The idea that live-in chaplains not only have physical access to residents, but also that university students themselves often have particular reasons to be vulnerable to clerics, is one that Dr de Weger stressed in his conversation with Observer.

“Some of my participants [in research studies] were abused at their universities,” he said, “and they mentioned their loneliness and how when the priest paid them some attention, they were slowly but surely sucked into the web.”

Emma told the Dominican Order.

Emma reported the priest’s sexual assault to the Dominican Order in 2008. By then, the priest had already been working at ANU for at least one year, in a position separate to his previous employment at the College. Emma was placed into the Catholic Church’s internal redress program at the time, ‘Towards Healing’.

Mediation sessions with a then-senior leader of the Dominican Order were a significant part of ‘Towards Healing’. Emma alleges that the leader revealed the priest’s employment at ANU during one of these mediation sessions.

“[He] explained to me that on his way to Canberra, he stopped by [the priest’s house] and asked him to sign the [priesthood resignation] papers because he had never signed. He said that [the priest] said he’s working at ANU, and that’s how I found out”.

“In a subsequent phone call, the [leader] told me he hoped I didn’t tell the public that [the priest] was now working at ANU”, Emma said.

Observer contacted the senior leader through a third party to request comment on two of Emma’s claims; that the senior leader asked Emma to not tell the public about the priest’s then-current whereabouts, and that he was aware of the priest’s whereabouts himself at the time.

In response to the first claim, the third party stated on his behalf that “at all mediations, the participants are warned by the mediator that the negotiations are confidential so that they can speak frankly. It is highly likely that such a caution was given by the mediator at the start of that meeting [where Emma was informed of the priest’s whereabouts]”.

Despite this, the leader “expressly denies making any statement that [Emma] not tell people about anything discussed.”

In response to the second claim, the third party confirmed that the senior leader was aware of the priest’s whereabouts. In a statement to Observer, they said “from memory, [the leader] believes that the person whom [Emma] complained about worked [at ANU] for a short period”.

Additionally, they confirmed – and defended – that the leader made a conscious decision to not inform ANU about the sexual assault report against the priest. “The person complained of had left the Dominican Order approximately 10 years prior to the mediation [between Emma and the leader] and had no further contact with the Order”, they asserted. “[The leader] did not contact ANU, or any other employer or associate of the person complained of, because he had absolutely no right to do so.”

Dr de Weger spoke frankly about how the failure to properly handle vital information when sexual assault reports are made has serious – and often avoidable – consequences.

When asked about what he believed the Catholic Church could do better to protect laypeople from experiencing clergy abuse, he said bluntly, “I don’t think that the Church takes their responsibility seriously at all when it comes to dealing with abusers”.

“Which then leads on to them, often, too often, abusing more people.”

Observer has found no indication that ANU was aware of the sexual assault allegation against the priest for the duration of his employment at the University.

Emma told ANU.

When Emma first contacted ANU independently in 2018, the priest was no longer working at ANU and he was last confirmed to be an employee five years earlier. She wasn’t fully certain of that at the time, but not for a lack of trying. Calls to various divisions and offices around ANU through numbers she could find easily online gave her a smattering of rumours about him and vague confirmations that he might have left ANU a while ago.

She exhausted some channels of communication to ANU until their absolute end; one directed her to make a Freedom of Information request if she wanted more information, whilst another accused her of violating Australian anti-spamming legislation and requested she cease contact.

It wasn’t for her own curiosity that she was asking so much. She had a list of recommendations ready to send to the right people at ANU, outlining what they could do for other potential victims of the same priest and how they could stop clergy sexual abuse from happening to another young adult altogether.

Emma described that her relative isolation from others as a result of her trauma meant that back then, and even today, she is “behind people in information.”

“I don’t have a network”, she said bluntly, “and you can imagine all my fear, because had I not been so crippled, and had I had so many friends and encouragement, I’m sure I would have come forward earlier.”

The first time she felt like she might have found the right people to talk to was when she finally reached ANU’s postgraduate student representative body, PARSA.

She had come across information about the Respectful Relationships Steering Committee, which described itself as creating pathways for issues relating to sexual assault and harassment at the University. The Steering Committee would later establish the Respectful Relationships Unit in 2019.

“I wonder in your work [at the Steering Committee]”, Emma asked in her first email to PARSA, “have you ever thought of promoting the reporting of sexual assault when committed by somebody who is religiously mighty and living amongst vulnerable students?”.

She said she wanted them to be aware of a predatory priest who used to work at the University, and described how she had been assaulted herself by the priest. Emma’s main concern was that “there may be victims of his who have yet to come forward”.

“It is very intimidating and shameful for victims of clergy sexual abuse to come forward because they are not always believed and supported. It can take years for the abuse to be reported. I am talking [specifically] about residential priests in John 23rd College who are supposed to support the spiritual life of students”.

Emma reached out to the undergraduate representative body ANUSA on the same Saturday, and sent them a list of recommendations for the Steering Committee. By that Wednesday, ANUSA had sent the list to a senior ANU staff member. Emma was copied into the email thread.

Students at one year anniversary protest of the “Change the Course” report.

The ANUSA contact seemed to initially misunderstand Emma’s connection to the University. ANUSA told the senior ANU staff member “[Emma] has contacted me after her experiences at ANU”, and that “she had proposed several actions that she would like to see responded to”. They further thanked the senior staff member for “discussing … how survivors of historical sexual assault at ANU could contact the university”.

This was only weeks after the one year anniversary of the Australian Human Rights Commission’s “Change the Course” report, during which ANUSA had criticised the University for the “very little” progress made on SASH policies since the report’s release.

According to Emma, the senior ANU staff member never replied to the email thread or her recommendations list.

Item #2 on the list was for John XXIII College to contact past and current residents for an inquiry into sexual assault by priests.

Item #3 called for students to be informed that seeking spiritual assistance does not warrant a priest taking advantage of their vulnerable state. Item #5 said students should be reassured that experiencing clergy sexual misconduct should not make them ashamed of themselves.

Item #4 requested that priests should no longer reside at the College.

Live-in chaplaincy remained at the College until 2020. John XXIII College has stated that the chaplain no longer lives on site because “they are no longer a member of the Residential Support Team”, and that the chaplain’s flat is now occupied by a Residential Support Team member who is not a religious leader in the Order.

Item #7 said that priests should pass a Working with Vulnerable People (WWVP) clearance as a precondition of their chaplaincy, and that the Dominican Order must work closely with the police to provide any history of a priest’s offences.

A broad policy on employee background checking at ANU was established in 2021, three years after Emma’s recommendations list was sent. The policy now requires all current and prospective staff to obtain a WWVP clearance, regardless of their main duties at the University. Prior to 2021, some staff members in “student-facing roles” may have already retained a WWVP check as a condition of their employment, but this was not a requirement of all staff members. Sexual assault is one of the offences that would disqualify an individual from the clearance.

John XXIII College today.

A spokesperson for the Dominican Order affirmed that the current policy for staff at the College, including the chaplain, does include WWVP clearances and “signed statements of conduct”. “The policies regarding John XXIII College are aligned with those of the University, as the College is affiliated with the University”, they said.

When asked precisely when it became a requirement for those in leadership positions at the College to obtain a WWVP clearance, and whether it was actually prior to the establishment of the 2021 policy, the Dominican Order spokesperson repeated that “the policy of the College would have been in line with that of ANU”.

When asked about the procedure for providing a priest’s offences to the police, the Dominican Order spokesperson stated that “as required by the requirements of the Catholic Church’s policies in Australia, all illegal matters are to be reported to the police in the first place, for the police to investigate.”

Emma forcefully disputes that this occurred in her case with the then-senior leader of the Order.

“No. He didn’t report it. The Church didn’t report it. He advised me at the mediation [that I could] report to the police but then it meant the Church wouldn’t pay me any redress because then the police/court process would take over”.

Emma filed a police report independently in 2018, several years after she had exited the ‘Towards Healing’ redress program.

Also on the day the recommendations were sent to the senior staff member, PARSA responded to Emma’s initial email informing them of her story. They were apologetic for what she had experienced, and commended her bravery. They also directed Emma to meet with the senior ANU staff member ANUSA had sent her recommendations to, alongside another senior member of staff. “In regards to the questions you have raised, [we] will make sure to bring this up at the next Steering Committee for serious consideration”, they said.

An officer from PARSA’s Student Assistance team reached out to arrange a conversation with Emma the following day.

The Student Assistance officer also seemed to initially misunderstand Emma’s connection to the University, alongside how recently she may have been assaulted. “We assist current ANU postgraduate students in a range of issues including academic, financial, disciplinary and sexual harassment/assault issues”, the officer began. “After reading the following email chain, I gather you are dealing with an ongoing sexual assault issue.”

A phone call between Emma and the Student Assistance officer was arranged for that Friday morning. Emma was optimistic about possible outcomes, emailing ANUSA and PARSA again to ask if somebody could accompany her to a meeting with ANU officials that she expected to happen soon.

By Friday lunchtime, when the misunderstanding had now been clarified, this outcome suddenly seemed improbable. Emma told Observer the Student Assistance officer “kept asking me if the abuse happened on campus” during the Friday morning phone call.

“When I said that it didn’t, they [said they] couldn’t help me”.

Emma’s takeaway from the phone call was that “the abuse did not occur on campus grounds, and it has nothing to do with students [since] I was not a student”.

Right after the call, Emma emailed ANUSA again. “I just talked with [the Student Assistance officer]. I don’t think that I will be meeting with either [of two senior ANU staff members]”, she said.

“I am happy that you [and PARSA] could raise my concerns at the next meeting of the Steering Committee. I don’t want the students to suffer what I suffered. Thanks for your help and listening.”

ANUSA responded in the afternoon. They promised to continue advocating to ANU “for clearer and more accessible policies for reporting sexual assault and harassment, and for the university to hold perpetrators of sexual violence to account”. They added the phone number and information for the Canberra Rape Crisis Centre.

Emma reached out again a little over two weeks later on a Monday evening. She was checking in on the Committee’s progress with her recommendations. ANUSA responded just over an hour later, to say that pathways for reporting and responding to historical allegations of sexual assault were discussed at the last Committee meeting, and that they “will continue to advocate for this pathway to be established”.

It was the last communication Emma received from anyone at ANU.

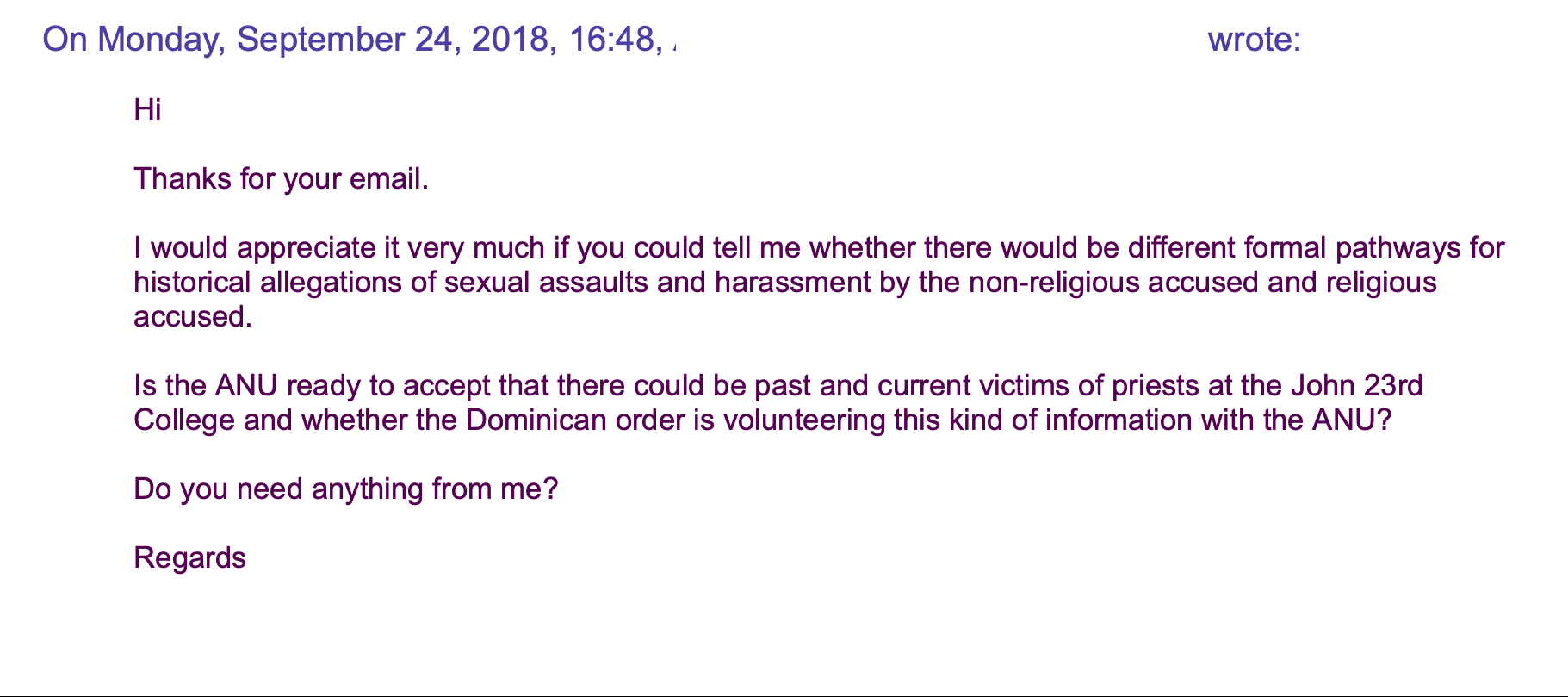

The next Monday, Emma ask if there were any “different formal pathways for historical allegations of sexual assaults and harassment” available, and if ANUSA needed anything from her. She raised the concern that the Dominican Order may not be volunteering all relevant information with ANU, and asked “is the ANU ready to accept that there could be past and current victims of priests at John 23rd College?”.

She did not receive a response.

Emma’s final email to ANU.

The current ANUSA executive has expressed that they were not aware of ANUSA’s correspondence with Emma until Observer’s request for comment.

“We were not aware of this email or these recommendations until we received your email … As best I can see, there was no email response from the ANU on this matter; while there is not a documentary record that ANUSA has located, it is possible that the follow up occurred in-person at the steering committee meetings. We have not been able to locate the relevant minutes in our archives either at this stage”.

“At this point, ANUSA cannot confirm if the measures that [were] recommended … have been undertaken”.

Of the various organisations Observer requested comment from for this article, only the ANUSA executive directly critiqued the treatment of Emma’s report.

“It is obvious…that the ANU should have taken steps to carefully investigate, both in its role in overseeing affiliated colleges, and to ensure there were no ongoing risks to the safety of students”, ANUSA asserted.

ANUSA also highlighted that the introduction of case managers for SASH incidents at ANU is currently in its early stages, and that extending this service to historical cases will be explored with the University once the service is understood to be of high-quality.

All parties involved in Emma’s story responded to requests for comment with the exception of the priest, who was reached out to through his brother. The priest’s brother did not respond to Observer’s request.

The Dominican Order and John XXIII College were contacted separately for comment by Observer for this story. Both parties were asked about policies in place at John XXIII College to protect students from sexual misconduct, and included an identical sentence in their respective email responses to Observer:

“The College has a comprehensive resident support team including a College Counsellor and a number of highly trained staff”.

The College response added that “all staff…are accountable to the College code of conduct, and all work to provide the best possible support structures and level of care to those who reside here.”

Dr de Weger ended his response to Observer paraphrasing Margaret Kennedy’s PhD thesis, ‘The Well from Which We Drink Is Poisoned’:

“It’s not because there is a vulnerable adult that abuse happens, but because there is a cleric willing to abuse that vulnerability.”

PARSA declined to comment on Emma’s claims about her experience with the Student Assistance team upon consultation with them. “We have to be clear that we cannot disclose any information about any student who has accessed our service, recently or historically”, they said.

An ANU spokesperson stated that the University “can’t comment on individual cases” when contacted by Observer. PARSA and the ANU spokesperson mutually highlighted that there is dedicated support available for disclosures of sexual misconduct.

ANUSA has expressed interest in raising Emma’s recommendations to ANU again. “It is clear that many of the recommendations are common sense measures to improve student safety at John XXIII and indeed across the ANU where applicable”, ANUSA said.

“The ANU needs to take an active role in ensuring that those staff that have power over students do not abuse their power.”

Emma, for her part, has tried her best to ensure that too. “My sons are now in their early twenties and one of them attended ANU”, she told us. “This really resonates with and motivates me to make the ANU in particular, and other Australian universities, a safe place for vulnerable young adult uni students”.

Universities Australia, the Sex Discrimination Commissioner, End Rape on Campus, SBS News, The Canberra Times, ABC, and the Governor-General of Australia are just some of the other figures Emma has contacted with her story over the past decade. Some she corresponded with for a period, some listened and apologised when they realised they could not help her, whilst others left promises of conversations with her unfulfilled.

Amidst her undeniable persistence to have her story heard, Emma’s life looks quite different today to how it did when it happened. If you asked her to share a little about herself now, she would say that her husband of 28 years is incredibly loving and cares deeply for their family. She would say that their sons prefer his cooking over hers.

If you asked her what her favourite memory was, she would tell you that it was when she was on a cruise, and a birthday cake was brought out to her as a surprise whilst everybody sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to her. She would add that travelling with her family makes her the happiest.

But before she told you all of that, she first and foremost would thank you for asking her about it at all. She would tell you that she deeply appreciated that the publication of her story ended refocusing on her.

–

You can read the Australian Human Rights Commission’s ‘Change the Course’ Report released in 2017 here.

You can read the ANU Women’s Department’s ‘Broken Promises’ Report released in 2021 here.

You can read ANU’s ‘Sexual Misconduct Reports and Disclosures’ Report released 2 March, and the ‘Student Safety and Wellbeing Plan’ released on 21 March here.

You can read the results of the National Student Safety Survey released 23 March here.

You can lodge a disclosure of sexual misconduct to ANU here; the incident can have occurred on or off-campus, recently or historically, and can involve somebody connected to ANU or where the alleged perpetrator bears no relationship to ANU.

–

If this article has raised any concerns for you, or you have been affected by its content, there is support available:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Beyond Blue: 1800 650 890

Broken Rites (support and advocacy for survivors of Catholic Church sexual abuse): (03) 9457 4999, [email protected]

Survivors and Mates Support Network (support for male survivors of childhood sexual abuse): 1800 4 SAMSN (72 676) Monday to Friday 9am – 5pm [email protected]

Bravehearts (support for survivors of childhood sexual abuse and their families): 1800 158 285

National Redress Scheme: 1800 737 377, Monday to Friday 8am-5pm AEDT

Canberra Rape Crisis Centre: 6247 2525 (7am–11pm) or 131 444 (after hours)

ANU Wellbeing & Support: 1300 050 327

ANU Counselling: [email protected]

–

Know something we don’t know? Email [email protected] or use our anonymous tip submission.

If you have an issue with this article, or a correction to make, you can contact us at [email protected], submit a formal dispute, or angery react the Facebook post.